Sample Essays

AFTER MANY YEARS AS A TECHNICAL WRITER and book designer (mostly obscure, esoteric stuff, often dry and full of big words and diagrams), I approached the editor at our little one-light town newspaper, The Bridgton News, and pitched a local column at him. I promise light fare: blow-by-blow descriptions of weather emergencies, narrations of repair projects on our old farm, entries from the journal of a frustrated northern gardener, and the like. “But what I really want to do,” I said, “is write about my family and about being a dad.” He mulled it over and politely said no. But about a week later he called and said, “Sure, we’ll try it.” That was going on nine years ago—two hundred columns, give or take. And every year the column has been awarded as one of the best in the state by the Maine Press Association. Yeah, well, we are a small state (from a literary perspective).

With the blessing of my editors, essays from my tenure at the paper will form the foundation of The Dad Story Project, at least at first. Eventually my stories will be overwhelmed by all the stories that all of YOU will write—which we will publish here. Click here to find out how to submit a story.

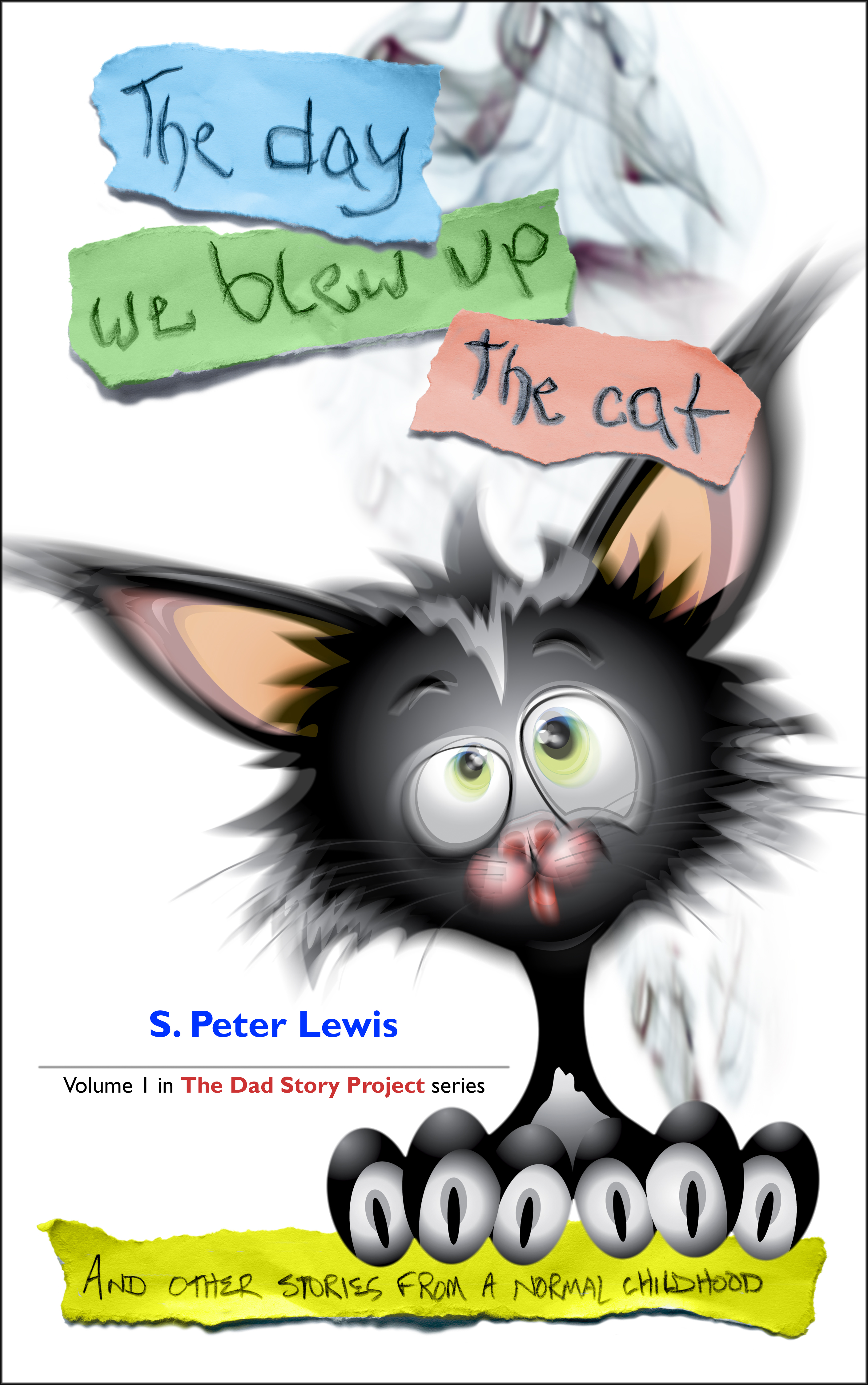

I will leave you with a few sample essays from the exploding cat book (where you will find a dozen more stories about growing up), and I hope they will make you smile—and perhaps get your own creative juices flowing.

Let’s celebrate fatherhood and childhood!

“I’ve worked with Peter Lewis off and on, and in various capacities, for over 20 years. He’s a pleasure to know, and a pleasure to read. And the Peter Lewis I know and the Peter Lewis I read are precisely the same person. Very genuine. Very enthusiastic. Very funny. And very full of life. These are the qualities that come through in his writings. In this hardened, cynical world, his columns truly are a breath of fresh air.”

Click the scribbling man to find out how to submit your own story!

Wanna read more?

I’ll refresh this page with new essays from time to time.

In the meantime, head on over to Amazon and download the first e-Book in

THE DAD STORY PROJECT series.

Click the exploding cat.

Just being there

I drove three hours through horizontal sleet the other day just to sit in a room and do nothing. But it was worth it, because as each slushy mile ticked by and with each passing minute I was that much closer to my son, who needed me.

My son, a college senior just a few weeks shy of getting his marine engineering degree, had been challenged. Something had happened and truth, justice, and accountability hung in the air like smoke—real enough, but hard to grasp. His honor and integrity were on the line, and although he held the high ground, he still wanted me there. So I drove on, slipping along the Interstate at 45 mph, passing cars in the ditches, sucking down coffee, and splashing a gallon of wiper fluid on my scummy windshield.

When I got to the school, I met my son and we walked together into a plush office. I sat quietly way in the back of the room, taking notes, peering over my glasses at the key players, and listening to my son’s strong and confident voice as he fielded tough questions and lobbed tougher ones back. I said almost nothing. I was just there.

At the end, after the tape recorder had been turned off, after the handshakes and mutual promises, my son and I went down into the tiny coastal village where his school was and sat on round stools at an ancient lunch counter. He ate a hamburger while I watched the man on the Weather Channel tell me I shouldn’t travel today unless I absolutely had to.

I’ve been a dad for almost a quarter-century and have pulled double-duty for the last 14 years (my daughter was born in 1992). It’s been the hardest, most wonderful, frustrating, fulfilling, painful, rewarding, draining, uplifting, challenging, and joyful job I’ve ever had. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Each morning since 1984 I have risen, washed my face, fired up the coffee pot, and stepped into the shoes of a father—shoes I’ve been expected to know how to fill. Some days I’ve nailed it and gotten the job done with ease. Other days I’ve been so baffled I couldn’t be certain the sun would come up the next morning.

I hung out that night at my son’s house with his roommates and friends, watching movies and eating cold Chinese food. I spent several minutes scraping crud off the cleanest fork I found in the sink. We sat on folding chairs and wrapped ourselves in blankets because the boys had set the thermostat just high enough to keep the water in the sink from freezing. Later, curled up in a sleeping bag tossed onto the floor of my son’s room, we talked long into the night, the room lit by a glowing globe he got on his tenth birthday. We just laughed and laughed until we both fell asleep.

The next morning the roads were clear. My son was headed back to campus and I was headed back home. It was awkward standing there at his front door, both of us saying silly things to keep the conversation going, secretly wishing we could ignore our responsibilities and just spend the day together. But we were grown-ups, father and son, and we both had things we had to do.

“Thanks for coming, Dad,” he finally said. And he smiled.

And that was it. I had never been more proud of him in my life. He was going through a tough time, but he was going to come shining through. He could handle things from here.

Being a dad takes faith, prayer, wisdom, tact, a sense of humor, self-discipline, empathy, stubbornness, the ability to say, “I was wrong,” and “I’m sorry,” and “Forgive me.” It takes insight and intuition, kindness laced with firmness, humility, late nights, early mornings, and every minute in between. Being a dad takes a pair of arms that open wide and pull a kid in close no matter what and with no strings attached. It can be the hardest work.

But this time all I did was sit in the back of a room—a quiet presence in the corner of my son’s eye.

Sometimes being a dad means just showing up.

The red knife

The man and the little boy looked down through the glass display case and saw row upon gleaming row of shimmering stainless-steel spectacle. On purple velvet rested knives of every imagination. Huge knives. Modest knives. Specialty knives. Knives with ivory handles. Knives for skinning, for whittling, for cutting rope. Knives for the sheath and knives for the pocket. And one stood out from the rest, tiny and red, its little blade scalloped and keen.

“That’s the one I’d want,” whispered the man, his hand on his boy’s shoulder. “Can you imagine having such a wondrous thing?”

“Yes,” the boy said, softly, his eyes never leaving the glimmering edge.

On a white tag tied to the handle with white string was the staggering price: twenty-five dollars.

The boy looked up, determined. “I’m going to save up for it, Dad,” he said.

For the next several weeks the boy scurried about in his off-time, bent on industry: mowing grass, helping his father build a shed, running errands for his mom, watching his baby sister; rushing from job to job, his pockets jingling with quarters and dimes, each night his jar slowly filling.

“What can I do today?” the bright lad would ask each Saturday morning, and then he would take his marching orders and hurry off to his tools and his toil. Always happy. Living in the dream of things wished for.

After a while, the man forgot about the knife. His work was hard and his days were long and filled with the troubles of industry and the troubles of others. He came home each night weary and quiet, bearing the invisible load of the hours on his shoulders, and fell asleep in a chair. In the next room, his little boy stacked quarters four-high and dimes in piles of ten.

One hot day the man came home from work early. He climbed slowly out of his old car and into the blazing afternoon. It was so hot he could smell the sun. And as he walked slowly and wearily toward the house and his chair and his nap before supper, his boy came running from the back yard, skipping and leaping and calling his name.

“Dad!” the boy yelled. “I did it!”

And the boy ran up to the man and said, “Hold out your hands,” and the man dropped his briefcase in the dust and held out his cupped hands and the boy gently laid in them the perfect small red knife.

“Oh, son,” the man said, the heaviness of the day magically lifting. “You did it.” And he turned the knife over in his hands and opened and closed its ambitious little blade and marveled at its craftsmanship. And then he marveled at the boy in front of him, craftsmanship of another kind, now happily wringing his little hands and rising up and down on his little toes as if about to fly away in a cloud of giggles and smiles.

“I am so proud of you,” the man said, folding the knife carefully and holding it out gently for his son.

But the boy didn’t take the knife. He put his hands behind his back. Looked down and scuffed at the dry brown earth. Wiped his dirt-smudged cheek against his shoulder. Then he looked up and squinted into the blazing sun, his baseball cap on a little crooked.

“I got it for you, Dad,” the boy said. Then he turned and ran off to climb a tree.

The man stood in his driveway holding the tiny gift in his trembling hands, his briefcase lying flopped over beside him in the dust of the burning day. And his tears fell through his fingers.

Almost twenty years later, the man tried to put down on paper the story of the little boy and the gleaming knife and the weeks of toil and the blinding sun and the weariness of a dusty afternoon, and he toiled hopelessly with nothing but words to describe how it felt to hold the love of his little son in his hands. And his eyes welled again as he remembered, and his hands trembled and vision blurred, and he leaned in close and strained to see the words as he typed.

And his tears fell through his fingers.

Confidence in a can of latex paint

I have a teenage daughter.

Amanda came to us in the usual way, all pink and wiggling, and within moments she held our hearts fast in her tiny fingers.

I wrapped her up in a blanket and brought her close.

“You can do anything, little one,” I whispered.

She was six minutes old.

Fast-forward fifteen years and she’s proving me right. Smart, assertive, charming, witty, tenacious—she’s got the world by the tail.

Ask Mandy what she’s going to be when she grows up and she says, “Whatever.” But it’s not the typical, flippant remark of a teenager, accompanied by the eye roll and toss of the hand. She really means it. Limits? What limits?

About a year ago, Mandy caught me into my office. “Dad, I want to paint my room.” A reasonable request, I thought, so I said, “Sure, sweetie, go for it.” But she wasn’t done. “I want to paint words on the ceiling, too.” I looked at her for a good long time, sizing up the situation, trying to figure out if this was one of those times when I should put my foot down, or let her go. I let her go.

The scheme was shades of purple, blue, and sea spray. Very aquatic. When you walked into her new room you felt like if you held your breath you might get a chance to swim with dolphins.

“Don’t you feel like you’re sleeping underwater,” I asked.

“Yeah, isn’t it cool,” she said.

And there, across the sloping ceiling, from wall to wall, were her words. Big, rounded, sweeping letters—bold pronouncements: Friendship, Passion, Optimism, Curiosity, Laughter, Love, Creativity, Hope, Loyalty, and Confidence.

Vibrant, colorful caterpillars strutted across the tops of some of the letters while huge, flamboyant butterflies flitted around near the walls. The symbolism was not lost on me.

“Gosh, Mandy, you’re amazing,” I said, pulling her in close.

Then, just three weeks ago, she said she wanted to paint her room again.

“Oh, but Mandy, what about your words?” I asked, trailing off into sadness.

Now she gave me the eye-roll. “Oh Dad, you’re such a sap. I can get more words, you know.”

So off she went with a fresh gallon of creativity, this time in flat white.

She appeared an hour or so later, sleeves rolled up, hair pulled back and held in place with a purple elastic, white splotches in accidental places, holding the brush with one hand cupped under the leaky end. There was no smile.

“Dad,” she said, bristling. “I just can’t get rid of my confidence.”

Sure enough, the white paint just wouldn’t cover it—that big, bold word kept oozing back to the surface. So I helped her and we put on another coat. And another. I tried going over the word with a stain-killing white primer, then another finish coat. “That ought to do it,” I proclaimed. Nope.

In the end, over the course of several days, we put over a dozen coats on that ceiling. On the last night, as Mandy prepared for bed, it finally looked like we’d won the battle. White. Everywhere, white. A clean, fresh start.

“What are you going to paint on the new ceiling, Mandy? I asked.

“Not really sure yet,” she said. “But it’s going to be great!”

When I came home from work the next day, there my daughter stood. Hands on her hips, toe tapping, shaking her head, and scowling.

“It’s back, Dad. My confidence is back. Ugh!”

I put my hands on her shoulders and looked deeply into those determined eyes. “Daughter, life is full of troubles. Persistent confidence is just something you’re going to have to live with.”